In the 19th century, thousands of immigrants left Wales to seek a better life in North America, settling in significant numbers in New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. By the time of the American Civil War, as the United States expanded westward, the Welsh were among the thousands of immigrants who crossed the Mississippi to settle in Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska and the Dakotas. Read a detailed history of the Welsh in Nebraska here.

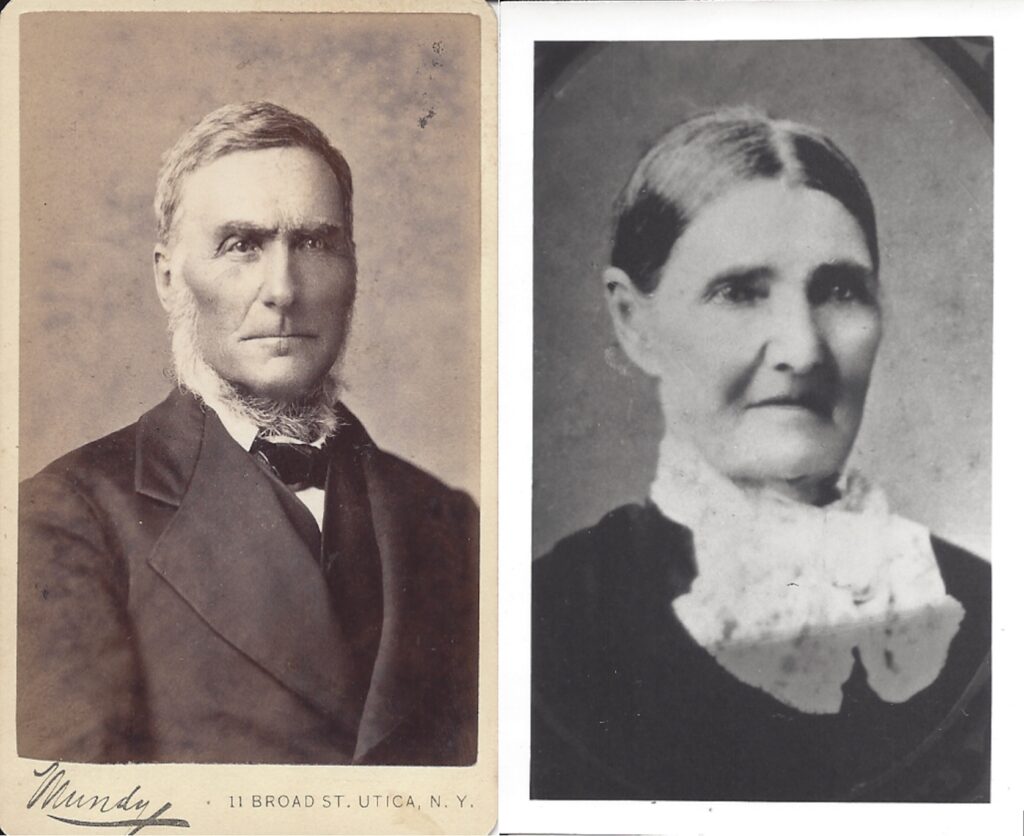

EARLY WELSH HOMESTEADERS IN NEBRASKAThomas and Catherine Higgins were among the first Welsh settlers to homestead in Nebraska. Thomas was an immigrant from Wales, while Catherine was born to Welsh parents in New York state. The couple lived in New York, Ohio and Wisconsin before homesteading in Nemaha County in the mid-1860s.

|

Encouraged to head west by railroads, state governments and their fellow settlers, they joined Americans from eastern states, Czechs, English, Germans, Norwegians and many other nationalities. To the north, Welsh immigrants also settled in the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

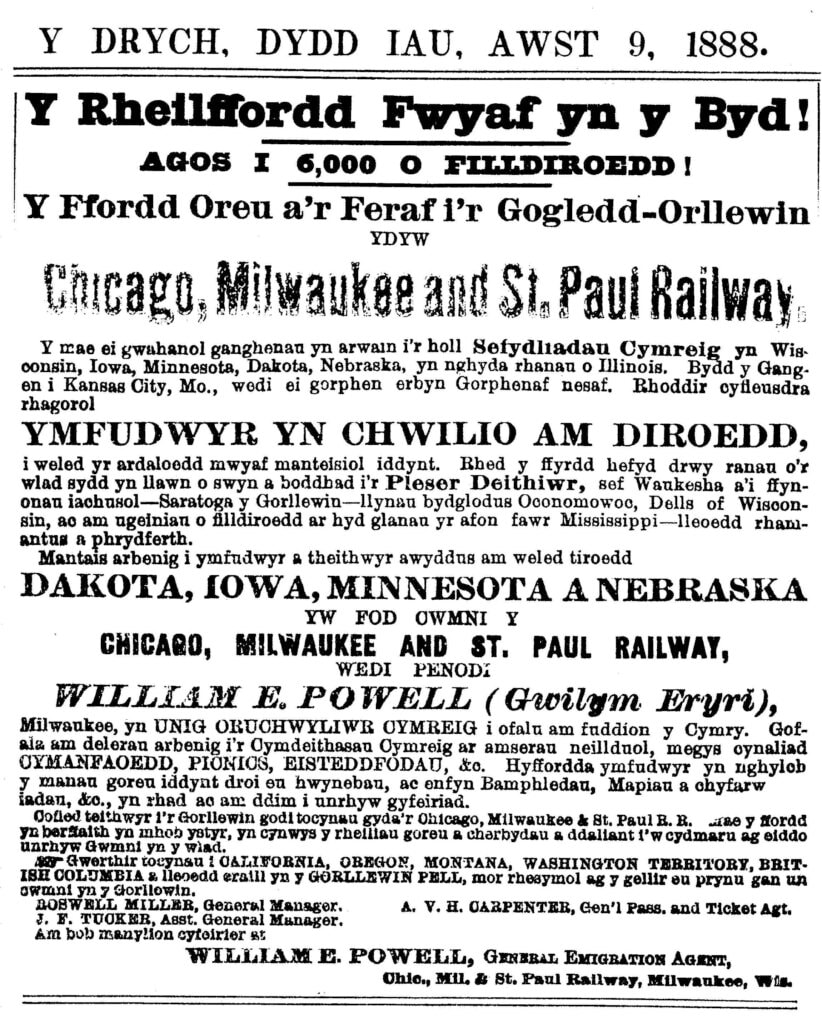

Welsh immigrants on the Great Plains were predominantly farmers, seeking the opportunities provided by the Homestead Act, which made it easy and inexpensive for settlers to claim government-owned (previously native-owned) land. Welsh-language newspapers advertised Tir Rhad (Cheap Land) and praised the fertility of the region.

Welsh immigrants on the Great Plains were predominantly farmers, seeking the opportunities provided by the Homestead Act, which made it easy and inexpensive for settlers to claim government-owned (previously native-owned) land. Welsh-language newspapers advertised Tir Rhad (Cheap Land) and praised the fertility of the region.

ENCOURAGING THE WeLsh to head westAn advertisement for the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway, promoting settlement on the Great Plains, published in the Welsh-language newspaper, Y Drych. The railroad's General Emigration Agent, responsible for assisting settlers, was William E. Powell, himself an immigrant from Wales.

|

It is important to acknowledge that the Welsh, like other settlers, displaced the native peoples of the Great Plains, by buying government land seized by force or treaty from the indigenous inhabitants. Recognizing this history is vital to reconciling indigenous peoples and the descendants of settlers today.

The Chief Standing Bear Trail, located just a few miles to the east of Wymore, commemorates the route taken by the Ponca Tribe when they were forcibly removed from their homeland, as well as the resistance of Ponca leader Standing Bear, who successfully argued in court for the right to return to tribal lands in Nebraska.

The Chief Standing Bear Trail, located just a few miles to the east of Wymore, commemorates the route taken by the Ponca Tribe when they were forcibly removed from their homeland, as well as the resistance of Ponca leader Standing Bear, who successfully argued in court for the right to return to tribal lands in Nebraska.

THE OTOE TRIBE and the welshSam Hudson, a member of the Otoe tribe, lived in the Wymore area during the period when Welsh settlers began to arrive, and was known to the Welsh. However, settlers, land speculators and local officials pressured the Otoe tribe to sell their remaining reservation lands in the 1880s. Some of that land became the Welsh settlement in the following years. Like most of the Otoes, Hudson was forced to leave Nebraska. He was later recorded in the census as living in Oklahoma.

|

In the early years of settlement on the plains, establishing a farm was hard work and conditions were challenging. The lack of wood on the prairies meant that some of the Welsh lived in sod houses at first. From South Dakota to Kansas, farmers struggled against droughts in the summer and blizzards in the winter. Grasshoppers and hail could ruin a harvest. Facing harsh conditions in the early 1890s, some of the Welsh requested aid from communities back east through Welsh-language newspapers and magazines. Some settlers decided to leave the Great Plains and migrate even further west to states such as Washington and California.

Eventually, with increasing settlement and technological innovations such as water-pumping windmills and agricultural machinery, the Great Plains would become an agriculturally productive region, and many of the homesteaders who stayed became successful farmers.

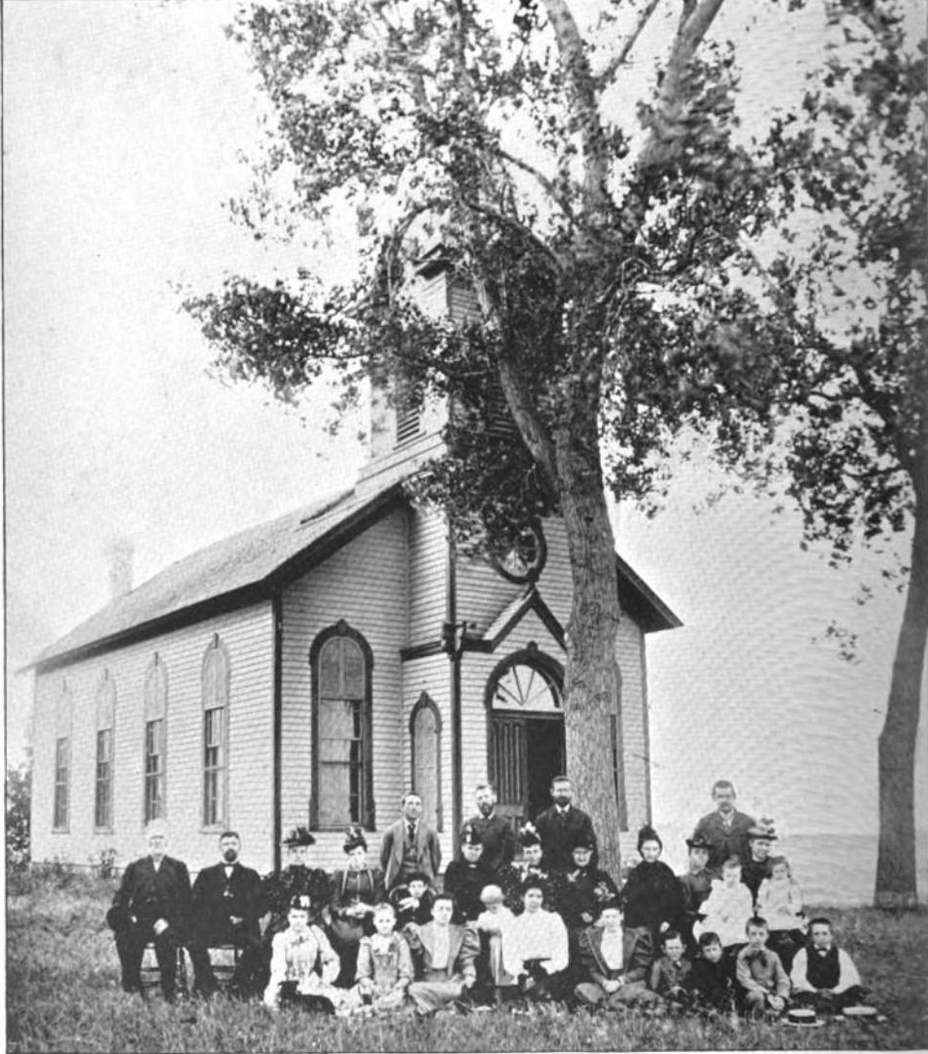

On the Great Plains, the Welsh lived in distantly scattered communities, but although their numbers were small, they maintained a strong sense of their identity. They worshiped at Welsh-speaking Congregationalist and Calvinistic Methodist or Welsh Presbyterian churches. Welsh communities stayed in contact with each other through Welsh-language newspapers, such as Y Drych (The Mirror). Welsh settlers continued to maintain the cultural traditions they had brought with them from Wales, including the eisteddfod, a competition of poetry and song conducted in Welsh.

On the Great Plains, the Welsh lived in distantly scattered communities, but although their numbers were small, they maintained a strong sense of their identity. They worshiped at Welsh-speaking Congregationalist and Calvinistic Methodist or Welsh Presbyterian churches. Welsh communities stayed in contact with each other through Welsh-language newspapers, such as Y Drych (The Mirror). Welsh settlers continued to maintain the cultural traditions they had brought with them from Wales, including the eisteddfod, a competition of poetry and song conducted in Welsh.

By the early 20th century, fewer immigrants were coming to North America from Wales. The younger generation of Welsh Americans and Welsh Canadians on the Great Plains were beginning to speak English more than Welsh, although the ethnic identity would remain strong for many years. Welsh churches would continue to sing hymns in Welsh and maintain many cultural traditions. However, as farming practices changed and rural population declined in the later 20th century, many of the Welsh churches would close or merge with other congregations.

Although the Welsh immigrants of the plains and their descendants were eager to assimilate into American and Canadian society, many have never lost sight of their connection to their ancestors. Welsh cultural organizations can be found across the region, keeping our history and traditions alive.

At the Great Plains Welsh Heritage Project, we welcome all to learn about the story of Welsh immigration to the Great Plains. As a regional history resource, we seek to engage with all cultures of the Great Plains, including other immigrant ethnicities and the native peoples for whom these are their traditional homelands.